Ladakh: Land of Irrevocable Change

The Land of High Passes

As the plane made its final approach to Leh, we glided over a myriad of nameless mountains belonging to the Shivalik, Pirpanjal, and Zanskar ranges. Slowly, we descended into the wide and dusty Indus Valley, flanked on either side by two steep walls of rock that seem to rise from nothing, and entirely barren besides a dusting of snow. This dramatic landscape more closely resembled the arid surface of a faraway planet and from what I'd heard, parts of the Ladakh region would feel as distant and untouched. A sharp u-turn around a low-lying peak took us flying past a shimmering monastery before landing at Leh’s International airport, where we were surprised to see a constant stream of ingoing and outgoing visitors; the quiet and remote places of Ladakh would have to be earned.

Ladakh means land of high passes but before venturing out to where people and oxygen are scarce, we had to acclimatize in Leh. We arrived in the morning and altitude sickness befell Luke by lunchtime, leaving me on my own to wander. I walked until I had a mental map of the old city, stopping to take in the bell shape of white gompas and the spinning of prayer wheels by passers-by. Aside from a short sojourn in Dharamshala, this was my first real encounter with Tibetan culture, which has long been present in Ladakh. Significant cultural exchanges occurred when waves of Tibetans spilled over the Himalayas and into the northern reaches of India; a mass exodus during China's Cultural Revolution (to which a two-storey mural near the market that clamours to 'FREE TIBET' stands testament). Two days passed quickly in Leh, our time spent winding through its alleys and museums; ducking into antique shops and turning forgotten artifacts over in dim and dusty light; strolling past the abandoned dwellings of the old town to explore the palace and the monastery overlooking the city.

Trekking the Markha Valley

Despite the treasure of Leh, our sights were set on trekking the length of the Markha Valley. Excited to be on the trail again, we naively set off with coffees in hand, foolishly strapping ourselves with extra waste to carry on the 6-day affair. Our first day of trekking brought us to Ganda La base and an elevation of 4200 m. Here we met Karl, the only other trekker we'd see that week. He was impressed that we were out there on our own; it was supposedly rare to see one without porters or guides. As the many signboards, advertisements, and trekking companies that clutter Leh signify, trekking has become a good sold to tourists. The next day, we caught one last glimpse of Karl before climbing over the 4900 m Ganda La pass; he was a tiny silhouette on a faraway ridge, and I was reminded that immersion in nature is best when simple and pure.

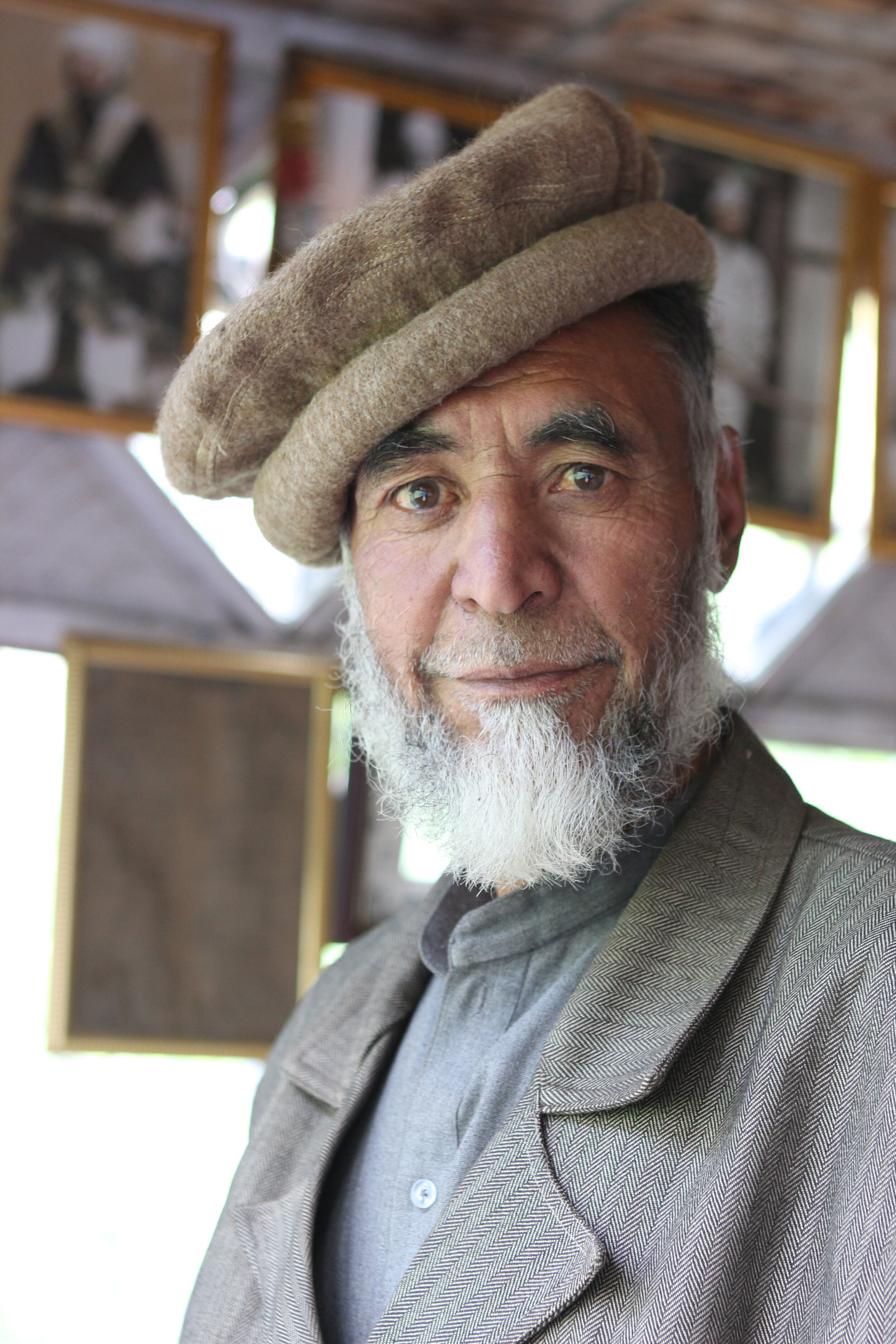

Each night, we camped in our trusty MSR Hubba Hubba (a 1.54kg 2-person tent) but that's not the only option on the Markha trail; the route is dotted by small villages and settlements which operate as homestays in the summer months in response to an influx of hikers who don't carry their own gear. When we arrived at Umlung (roughly mid-way), we were greeted by three farmers as they drove two oxen and a wooden plow to furrow their field. We ate at their homestay, to contribute to the local economy and take a break from cooking in a tiny pot balanced precariously on a pocket stove.

Ladakhi kitchens are the heart of the household and so there we sat, cross-legged on floor cushions at a low hand-painted table, while Thundup extended our Ladakhi vocabulary (donkey = boombu). He poured home-brewed barley beer into our porcelain teacups and we adopted his custom of toasting. For every refill poured, we were required to clink cups, drink a sip with Thundup looming over eagerly, then allow the cup to be filled to the brim once more. Thundup's Ladakhi music played from a small speaker charged by a wire dangling from the ceiling; 'solar panel' was one of the words in his arsenal of English. Besides this piece of technology and the pink polish on his daughter's fingernails, everything else was done as it has been for centuries: water for our chai fetched from the river, our dinner of lentil daal and rice stirred over a wood stove fire.

A few days and some kilometres later, we awoke on a wide and windy plain called Nimaling, which sits in the cold shadow of Kang Yatse (6400 m). We set out on our final push over the Kongmaru La pass sunburnt and wind-chapped, passing men collecting yak dung to burn for heat as has been done on that very plain for centuries. Reaching prayer flag-ridden apex of the Kongmaru La (5260m) and looking straight down into the valley, the Markha appeared as a distant mirage, blurring like a dream about to slip away. That thought that we would probably never return weighed on me. I was deeply moved by the Ladakhi's traditional and sustainable way of life, realizing all that we'd observed lies on the edge of abandonment.

Ancient Futures

Recovering from journey within the comfortable confines of Coffee Culture, I flipped through a book called Ancient Futures in which a British woman depicts the "saner way of life" she observed living in Ladakh. She describes the alarming rate of change she saw over a period of 18 years, connecting it largely to tourism. The Indian Government introduced tourism to Ladakh in 1974 in a political move to put its stamp on the region that was once controlled by Pakistan. Until then, Ladakhi culture was well-preserved by the natural border created by the area's inhospitable climate and landscape. When trade over the mountain passes was conducted by foot or on horseback, change from outside influences such as Tibet occurred slowly and on Ladakhi terms, allowing for adaptation from within and resulting in a unique fusion of culture that is a celebrated part of Ladakh's identity. But roads and airports and internet cables ensued in the 80s and 90s, causing rapid cultural change. New opportunities drew more people away from their villages to rapidly expanding city centres.

As we walked between villages in the Markha, we observed a road in the making; it struck us that change was on its way to the few villages still disconnected from the grid. Today, Ladakh is still largely cut off from the rest of India for roughly 7 months of the year as the winter climate is too harsh for travel by road. But on the day we returned to Leh from our hike, Indian president Modi announced the construction of a new tunnel to connect Leh year-round—as if to affirm that change is inevitable. Once independent and out of reach, Ladakh is now controlled by faraway forces: the Indian government with its different viewpoints, and western ideology as it streams in through internet cables run over the mountains (maybe it's a silver lining that wifi is still incredibly intermittent).

Perhaps, the dilution of Ladakhi culture is best shown in Ladakhi's loose and poetic descriptions of time: 'nyitse' literally means there is sun on the surrounding peaks, 'gongrot' refers to the period between nightfall and bedtime, and 'chipe-chirrit' means 'birdsong', referring to the early morning before sunrise, when birds sing. These phrases are bound to disappear as connectivity, technology, and rising tourism puts Ladakh on the same 24-hour clock that we are bound to.

I remain deeply changed by the age-old ways of the Markha, by a short hiatus to a simpler time. 6000m peaks were not only a sight to behold, but offered space and freedom to exist in a most simple and primordial way. I lost track of time and unnecessary constructs like societal expectations or the perpetual self-comparison that comes with social media. I was simply washing dishes in the river as nyitse faded, reading my way through gongrot by the light of a rechargable headlamp, and waking up beside my partner in the dewy light of chipe-chirrit.

Most importantly, I was disengaged from the trappings of our modern, wasteful, and irreverent society long enough for something to click.

Lessons from India

When I think back to my time in India, my mind races with sound and smell and colour—sweet and spicy incense, pastel Hindu temples, jewelry-adorned faces, and walking across postcard-perfect scenes. Until recently, my life was beating with the unmistakable pulse of India.

India, where rain trees swoon over crumbling colonial buildings whilst bright saris cling to women hunched over as they sweep an eternal cycle of leaves. India, where a man frees a dress shirt from wrinkles with a coal-heated iron, hands piloted by muscle-memory and a work ethic inherited from his father. India, where lost loved ones are industriously burnt to ash and bone then swept into the sacred Ganges. Darling old India, with one foot firmly planted in the past and the other launched so far ahead it's impossible to predict where she's headed. India, where beauty, struggle, tradition, progress, inequality, freedom, inefficiency, and innovation exist all over and all at once.

Whenever I think of India, my heart swells with nostalgia. I was fortunate to spend six months balancing uninhibited travel, freelance work, and family time in Bangalore. Being a guest at the Wilson residence was not only an unconventional way of 'meeting the parents', but the inspiration to backpack and settle in a new country as they had done in the 80s (long before wifi, online bookings, and Google maps—Bruce and Terry Anne are the real deal). This time was also spent working alongside Terry Anne, a published author who transformed the living room from a family place to a creative space daily. Much more than a window of unique experiences—of gazing up at the Taj Mahal, scooting to the hidden beaches of Goa, watching sunsets atop Hampi's tallest boulders, and dancing in a sea of people and colour at Holi festival—India was a time of personal growth.

Surprisingly, the challenges of living in India turned out to be an even bigger gift. The challenge wasn't in avoiding scams or food poisoning, but in understanding another culture. While India leaves a newcomer rich with treasures to uncover, it also leaves one with much to reconcile. Living in India, I was constantly internalizing signs of inequality and poverty—constantly overwhelmed by the amount of garbage and lack of government infrastructure; constantly bending my understanding around age-old and unfamiliar traditions (such as the mention of preferred castes in newspaper marriage ads). A sea of contradictions was ever-present to navigate: so much kindness, yet so much indifference; so much wealth, but such disparity; immense beauty, yet inadmissible hardship. India lived up to my preconceptions of being a diverse and complex macrocosm, but I had naively expected to gain an understanding of these nuances in a mere six months. Now gone, I look over my shoulder finding India more difficult to describe than when I had first arrived.

While I stutter over summing up India without sounding cliché, one thing is certain: my perspective on travel has changed. In the past, I was driven by 'making the most' of my time in new places. I came, I saw, and I conquered without truly considering what was left in my wake. I think back to trekking across Denali National Park, a vast expanse of the Alaskan wilderness. With the presence of wild animals like grizzlies and the absence of marked trails, visitors are required to watch a safety video instructing trekkers to spread out rather than walk in a single file line to minimize trampling. I had been genuinely concerned with this while exploring the park, but it never occurred to me that by gallivanting to popular destinations around the world, I was also just trampling other fragile flowers.

Ladakh faces a period of irrevocable change, and so do I. My biggest takeaway from six months in India is acceptance that wanderlust gypsy I have largely identified with is at odds with the environmentally-conscious human I strive to be. I value travel for its unique ability to challenge me, to widen my understanding of the world, and to pique my curiosity. But I understand the urgency at which we must preserve our planet and fragile communities like those in the Markha Valley—a feat that will require both systemic change and personal growth. I’m excited to embark on this journey…